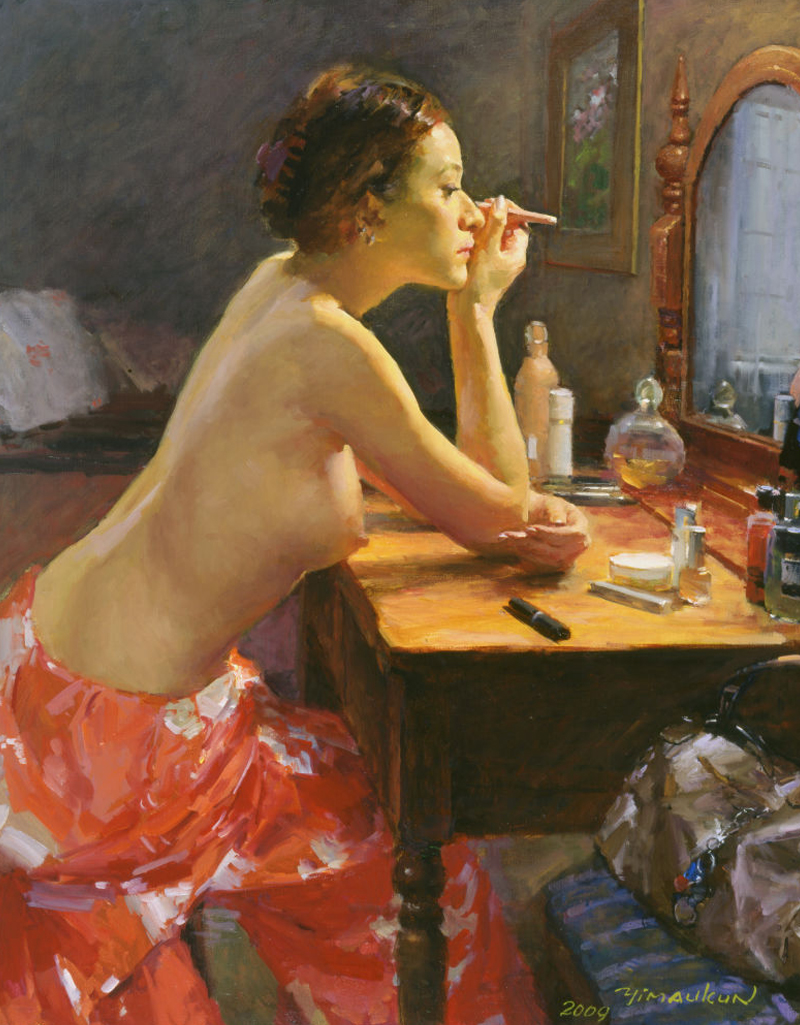

Narrative

Westside Evening

Oil on Canvas

116.5x80cm

2010

When I first arrived in Taipei during the 1980s, I came by myself from Hong Kong to make oil portraits for people living in Taipei. Sometimes I would go with friends in the evenings to the bustling Ximendingdistrict for dinner and music. In those days, there were several Western-style restaurants of various sizes in Ximending. All of them featured a stage, lighting, and sound equipment. In the evenings, the lights would come on, the music would play, the singers took their turn on the stage, and you could hear their faint strains in the streets and alleyways. The Taiwanese singing style inherited the tragic air of Japanese music. Pent-up stress meant that they often sounded even more anguished and reminded me a lot of the old traditions. The singers on the stage seemed to have their own laments as well.

In 1987 I painted from memory a 50-cm painting titled Who to Love. These traces of the old days are now gradually fading away from Ximending and the music restaurants are disappearing one by one as well. The voices of singers like Jiang Hui and Lin Huiping that I heard at “Xilishi” (Western Warrior) and “Jinche“ (Golden Chariot) twenty years ago still haunt me, however, so I struggled with the paint brush to recall those scenes of yesterday. It is my way of coping with the nostalgia for a time gone by.

Before I knew it, another twenty-or-so years had passed!

Death of Concubine Yang

Oil on Canvas

180x150cm

1999

The romance between Emperor Xuanzhong and Concubine Yang during the Tang Dynasty has long been a household story in China. The decade during which this romance took place, however, was dominated by increasing corruption and misrule that eventually triggered the An Lushan Rebellion. In the poem Song of Everlasting Regret composed by Bai Juyi, the section on “six armies stayed in place” was set at night in a small Buddhist shrine attached to the Maguipo post house. I depicted the scene shortly after the death of Concubine Yang by strangulation to explore one of the most gripping yet tragic scenes in history. Using the Western oil painting techniques for light and shadow, I made time stand still for Concubine Yang, Gao Lishi, Chen Xuanli, XieAman, and the palace servants under the candlelight.

I am not sure exactly when I was struck by the idea for this painting now. I began working on the draft in 1989 and most of the changes were made to the pose of Gao Lishi and the background. It was 1999 by the time I decided on the final draft! During this time, I asked many friends to model for me, studied the historical records, searched for props. . . . I enjoyed the struggles of creating a historical painting as well as the sense of relief upon completion in full measure.

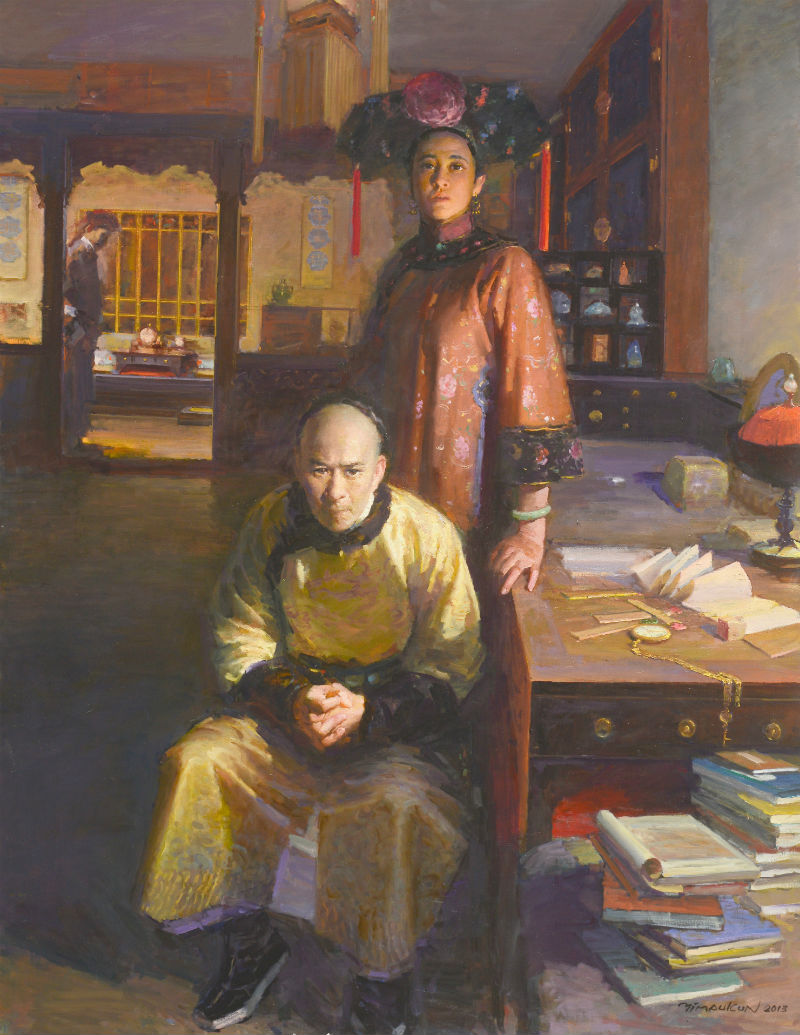

Emperor Guangxu and Consort Zhen

Oil on Canvas

145x111cm

2013

Emperor Guangxu was one of the tragic characters in modern Chinese history. Smart, studious, and progressive, he realized after the First Sino-Japanese War that the burden of reforming China rested on his shoulders. Determined to make changes, he launched the Hundred Days’ Reform and for a while the people were filled with new hope for the future of China. Guangxu, however, did not have any troops of his own. Kang Youwei and other supporters thought Yuan Shikai was on their side and wanted him to put Dowager Empress Cixi under house arrest when she went to Tianjing to inspect the New Army that Yuan had trained. Yuan betrayed their plot to Rong Lu who then directed Guangxu to be exposed as well. When Guangxu received word of this betrayal, he immediately told Kang Youwei and the others to escape while he himself stayed behind to face the consequences in the palace. The next day, Cixi summoned Guangxu to an audience where he was harangued by court officials loyal to the conservatives. Guangxu was then deposed and confined to Yingtai. Cixi also ordered Consort Zhen to be imprisoned in a small room in the northern part of the Forbidden City. When the Boxer Rebellion broke out and the Eight-Nation Alliance captured Beijing, Cixi fled west taking Guangxu with her. As they were about to leave the palace, Cixi ordered Consort Zhen to announce that the emperor was leaving the palace. Consort Zhen replied: “The Emperor is not leaving. He shall stay in command at the Capital!” Such righteousness! Such clearness of mind! Cixi immediately order the grand eunuch Cui Yugui to force Consort Zhen down a well and drown her. When the imperial train finally returned to the palace after their “Western Hunting Trip,” Consort Jin ordered Consort Zhen’s remains to be retrieved from the well and given a proper burial. When the Emperor asked if she had left behind any belongings, he was given only an old mosquito net. Guangxi brought the mosquito net to Yingtai and kept it with him until he took his last breath.

The night before the coup, Guangxu only had Consort Zhen by his side there in the sleeping chambers at the back of the Hall of Mental Cultivation. How did Guangxu and Consort Zhen pass that long night? Whenever I made changes to the face of Guangxu yet again, I always felt a deep sense of sorrow. Guangxu was the only emperor in the history of China to truly want to bring about political reform. In this he was like no other emperor.

Twenty-four years passed from conception, draft, to the final oil painting! Even today, whenever I talk to other people about that night in the Hall of Mental Cultivation I am still choked with tears. I was not just painting history. I was grieving for Guangxu!

Evening Spring Rain in Taipei

Oil on Canvas

130 x97cm

1993

When I first arrived in Taipei in the mid 1980s, I rented an apartment on Chongqing South Road and also purchased a second-hand bicycle to get around. One day, I was passing by Taipei First Girls High School when I saw a girl using the payphone. She had a large bag slung across one shoulder and was leaning against the wall with her feet crossed while she talked on the phone. I parked my bicycle and made a quick sketch. From then on, I often thought of the girl using the phone.

One day, a friend from a vocal backing group gave me a ticket to a Pan Yintze concert. After the concert, I started walking through the arcade on Zhongshan N. Rd. There was a slight drizzle in the air that gave the street lights a hazy glow along with a payphone hanging quietly on the arcade wall… Aha! That girl should have been making the call here! I found a model to make a sketch, took several photos, and even went back to Zhongshan N. Rd… Who was the girl talking to? How long did they talk for? What were they talking about? Absolutely no idea! There was just the evening in the Spring rain, the arcade lit by lights, and that girl connected to someone in the distance…

Mackay Practicing Medicine

Oil on Canvas

120x96cm

1996

George Leslie Mackay (1844-1901) is a well-known historical figure in Taiwan. He was a Canadian missionary and licensed dentist. Apart from his dental practice, he also opened hospitals and schools, mastered the language, married a Chinese woman, and was ultimately buried in Taiwan.

There are still many historical photos of Mackay on display at the site of Fort Santo Domingo in Tamshui, Taipei. One of them shows Mackay and his assistants pulling teeth for a long queue of farmers. Mackay had studied dentistry in Toronto and was a licensed dentist. He ended up pulling more than 21,000 teeth from patients in Tamshui! The dentistry tools he used are now preserved at Danjiang Junior High School.

I was invited to participate in an exhibition on Tamshui’s history and culture and decided to create a painting on Mackay and named it Mackay Pulling Teeth. After the exhibition, I felt that this topic could have been presented in a richer and more lively manner. So I redrew the draft and mobilized my family members to be my models for checking the pose and lighting: My son was Mackay, I was the farmer with toothache, my wife was the farmwife with toothache, and my daughter became a little village girl… I named the completed painting Mackay Practicing Medicine. This painting is part of historian and novelist Li Ao’s private collection and featured in his article “From Mackay Practicing Medicine to Andrew T. Huang” which was published in a supplement of the Yancheng Evening News that year in 2008.

Crossing the Stormy Strait (Taiwan’s Forefathers I)

Oil on Canvas

300x160cm

1996

Taiwan is mainly an immigrant society. Starting from the early Qing Dynasty, for more than three centuries people from the lower classes of society living on the mainland coast continued to brave the sea ban imposed by the Qing government, as well as the strong winds and high waves of the Taiwan Strait – or the “Black Trench.” Who knows how many lives were swallowed by these waters? How many made it against all odds? Eventually, they made it to Taiwan where they started a new life with nothing more than the clothes on their backs and opened a new chapter in the history of Taiwan.

The history of Taiwan’s forefathers inspired a great deal of creative interest in me. It allowed me to give free rein to my imagination without being influenced by historical photos. I started out by making a small draft then traveled to Fujian in China to visit Xiamen, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Meizhou Island and Dongshan Island. There I toured the fishing harbors and farming villages to collect a great deal of reference materials on appearances, clothing, and the shape of the boats. Back in Taipei, I first made a large drawing and then invited models to verify all of the important characters. I then worked for four straight years to complete the Cross the Stormy Strait and Reaching Shore in the Taiwan’s Forefathers series.

Reaching Shore (Taiwan’s Forefathers II)

Oil on Canvas

300x140cm

1995

This was actually the first of the two paintings in the series to be put to canvas. The composition was finalized early and the characters decided upon right away as well. Listening to a performance of Nanguan music in Quanzhou park drew my attention to the fact that someone probably brought along their erhu. The hiring of Fujian master craftsmen at great cost for the rebuilding of Longshan Temple made me pay attention to how carpenters should look. When I saw Professor Qin Changan from the Department of Fine Arts at Xiamen University, I knew right away that he was that carpenter. “Mazu” and a sailing ship were also essential as well.

In 2005, I completely repainted the painting. I removed the man with the outstretched arm then added two more. For the man with the red bandana, I asked a reporter from Yilan to be my model. I paid particular attention to the woman carrying her belongings on shoulder poles. I made her the mother figure of the Taiwanese people: beautiful, hard-working, determined…

I wanted to express how the people were filled with hope and joy when they reached Taiwan after the storm. Here they will build a new home.